Patients With SUDs Want Options. Don’t We All?

Jim Winkle has a lot of experience with Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT). He’s designed clinic flows, trained hundreds of healthcare providers, worked on a wide range of implementation issues, and, in the process, come to recognize a number of shortcomings of the SBIRT model.

As an early intervention strategy for people with risky or addictive substance use, there are ways that SBIRT just isn’t working. Most glaring of these is the “referral to treatment” portion, wherein providers are supposed to connect patients to addiction specialists for follow-up care. Patients are not following up on these referrals to specialty care, as many providers have seen anecdotally and as a meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled trials showed in 2015.

However, healthcare providers must do a better job working with patients with substance use disorders (SUDs) because SUDs are so common and affect a patient’s overall health. Furthermore, because people with SUDs very rarely go to specialty addiction treatment (like a 28-day rehab or a methadone program), healthcare providers are an important line of defense against the consequences of substance use, including fatal overdose.

In December 2019, Winkle hosted a webinar titled “How Harm Reduction Fits Into the SBIRT Model.” The full presentation is available on-demand and the slides have been posted for further reference.

In this webinar, Winkle does not suggest throwing the baby out with the bathwater, or abandoning SBIRT completely. Rather, he offers several tweaks to traditional SBIRT protocols to make them “harm reduction-informed.” Because, as Winkle points out, “Patients with substance use disorders want options.” Don’t we all?

The Damaged Relationship Between People Who Use Drugs and the Healthcare System

Before getting into the nuts and bolts of a harm reduction-informed SBIRT model, Winkle discussed the damaged relationship between people who use drugs and the healthcare system. How does it feel for a person with an SUD to seek medical care? Often, it feels terrible.

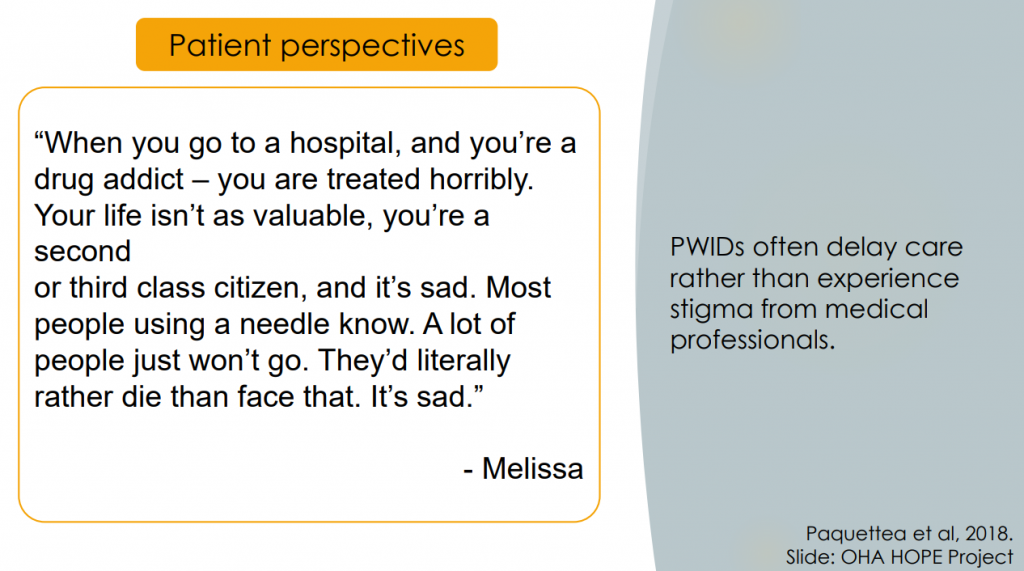

Interviews show that people who use drugs feel intense discrimination, which often aggravates a sense of internalized stigma. The experience can be so negative that it’s a serious barrier to seeking care. In the words of one respondent:

When you go to a hospital, and you’re a drug addict – you are treated horribly. Your life isn’t as valuable, you’re a second or third class citizen, and it’s sad. Most people using a needle know. A lot of people just won’t go. They’d literally rather die than face that. It’s sad.

Any provider who wants to help people with SUDs needs to appreciate this context.

Many Ways Primary Care Can Help Patients with SUDs

The traditional SBIRT model assumes that a patient with an SUD should follow one of two paths: either to reduce their substance use or to abstain completely. However, there are lots of ways a primary care provider can help patients with SUDs besides recommending these two options. Winkle offered the following list:

- Screen for unhealthy substance use

- Treat complaints related to use

- Discuss reducing harm from use

- Offer medications for SUDs, PrEP, treat HIV, treat HCV

- Provide general care

- Help patients forge a path to recovery

- Enhance the patient’s motivation to change behavior

Many of these strategies could be described as “harm reduction,” in the sense that abstinence is neither prioritized nor assumed to be the patient’s goal. It is possible that these interventions will lead a patient toward some version of recovery, but even if not, these strategies are likely to improve the patient’s health.

Key Tweaks to Make SBIRT Harm Reduction-Informed

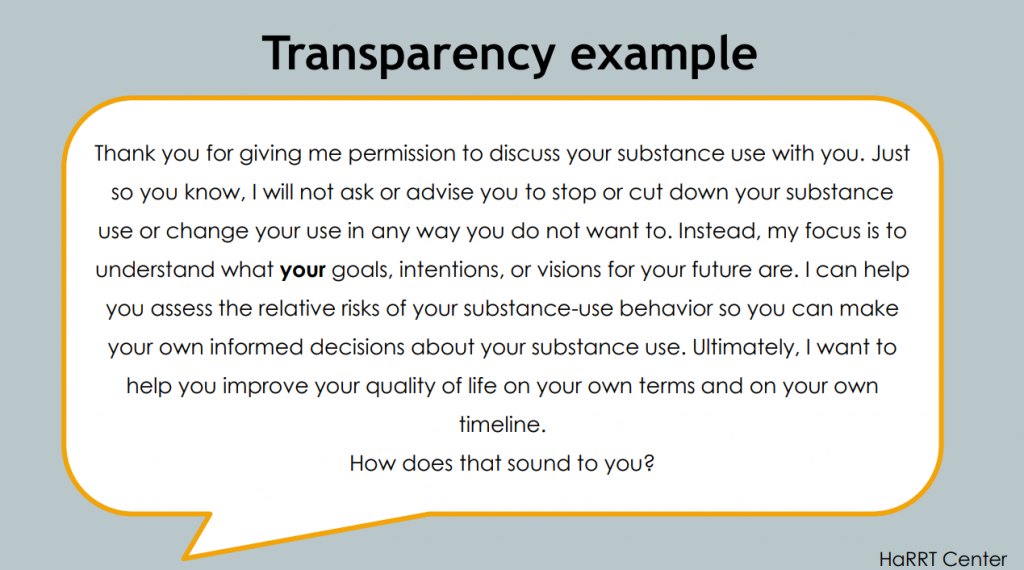

Winkle proposed several tweaks to the traditional SBIRT approach. One was the addition of a statement about transparency. He suggested that after a clinician has asked permission to raise the subject of substance use, the clinician then take a moment to explain their role.

With the help of the Harm Reduction Research and Treatment Center at the University of Washington, Winkle devised this sample script for a clinician to be transparent about their role:

Thank you for giving me permission to discuss your substance use with you. Just so you know, I will not ask or advise you to stop or cut down your substance use or change your use in any way you do not want to. Instead, my focus is to understand what your goals, intentions, or visions for your future are. I can help you assess the relative risks of your substance-use behavior so you can make your own informed decisions about your substance use. Ultimately, I want to help you improve your quality of life on your own terms and on your own timeline. How does that sound to you?

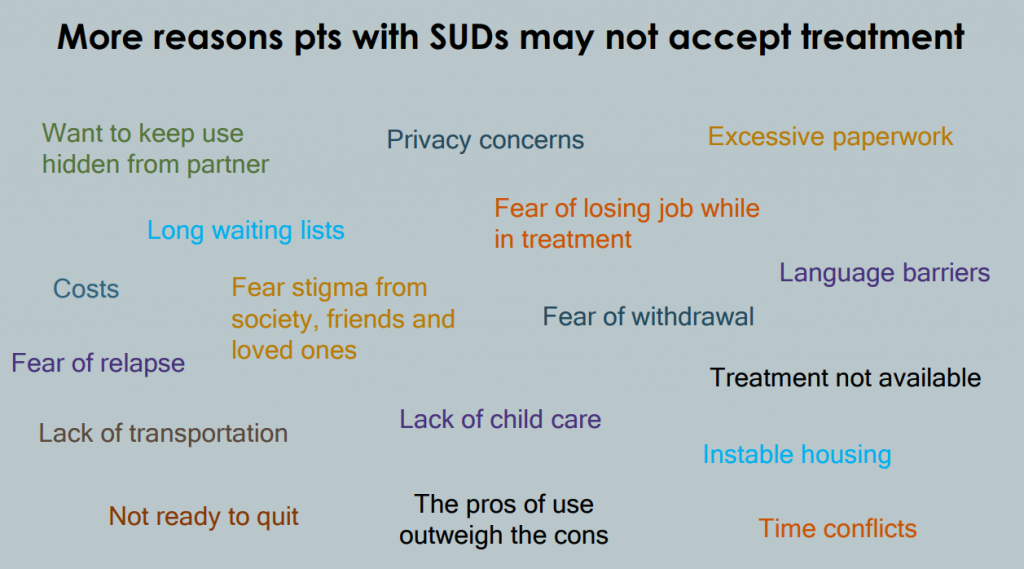

Winkle also proposed a radical reconfiguration of the “referral to treatment” in SBIRT (which, as we know, is not working anyway). The traditional approach to treatment referrals is clinician-driven, not patient-driven, he said. This is backed up by consistent survey data showing that almost everyone with an SUD does not believe they need treatment. This belief, combined with numerous other practical barriers, makes it clear that a patient only actually wants a referral to specialty treatment once in a blue moon.

Winkle proposed that the “RT” be changed to ongoing engagement in primary care. Rather than “making the patient somebody else’s problem” (which is both dismissive and ineffective) primary care providers should measure the success of their SBIRT interventions by the extent that the patient is willing to come back to their office. At these appointments, the primary care clinician can work with the patient on any self-directed goals with regard to substance use. The clinician can continue to share safer use strategies and use Motivational Interviewing techniques to elicit the patient’s desire for behavior change, should it exist.

As support for this reconceptualized treatment referral, Winkle pointed out that the National Council’s most recent SBIRT Change Guide has moved in a similar direction. In this guide, RT has been eliminated and replaced with “management” of SUDs through “repeated visits for brief counseling and shared decision-making.”

Providers Must ‘Flip the Expertise’

“By taking a harm reduction approach, we are reinforcing a patient’s autonomy, self-respect, and self-efficacy. We defer to their wisdom. They know the context of their lives—not us,” Winkle said.

For any healthcare provider, this often requires a “flip” in the middle of the clinical interaction, which can feel uncomfortable.

Speaking to clinicians, Winkle said, “You are the expert if it’s a healthcare visit, but when we start to talk about the patient’s behavior with their permission, the roles switch and suddenly they are the expert. And you have to be comfortable with that.”