John has been sober since November 24, 2008.

“I never did drugs,” he said. Then he pinches together his forefinger and thumb, placing them at his mouth, making the pretty much universal sign for smoking marijuana. “Ok, I smoked a little.” He signs a bottle tipped back into his mouth. “But alcohol was my real problem.”

John is Deaf and part of a community that rarely has an easy time finding services for substance use and/or mental health disorders. “Deaf people with mental illnesses must focus,” he said. “AA was very important part of helping me to focus.” Without the 12 steps, he tells me, he’d still be drinking.

The Big Book is also important to him—he signs “book” and immediately I picture the Big Book with its dark blue cloth cover—but he doesn’t read the printed, English version. It’s not written in his language, which is American Sign Language (ASL). He knows the stories because he “listens” to them in his own language that interpreters sign at meetings.

“These stories,” he said, “are so important to me because I can relate to them.”

Before he got sober, John had been in and out of recovery for years, explaining that it didn’t work then “because I wasn’t ready.”

“I was dishonest with myself. Now I cherish my recovery and my freedom.”

John is a success story, fortunate to have found support at places like Milestone Centers, Inc, a behavioral health center that provides services for the Deaf and others with disabilities. There are few Deaf-friendly AA meetings in Southwest Pennsylvania; John attends one where an interpreter volunteers her time to make AA accessible for him. While he didn’t complain of difficulties accessing treatment and support as a dually-diagnosed Deaf person—his gratitude is effervescent—there are other Deaf, Deaf-Blind, or Hard of Hearing (HH) persons who for many reasons don’t receive the substance use treatment and support services they need.

Real need, difficult to calculate

A 2012 review concluded that substance misuse may be nearly as frequent in Deaf individuals as in hearing. One study that compared a Deaf and HH group with a control hearing group, found that the deaf group used substances earlier and their misuse was more severe than in the hearing group.

But it’s not easy to tell exactly what the needs are in terms of substance misuse and disorders among the Deaf and HH. Published information is piecemeal and comes from small samples from discrete areas; there is no centralized database from which to draw statistics.

Although prevalence data is weak, we know there are many Deaf individuals in need of (and seeking) substance use services. Below is a synopsis of what researchers–and the southwest Pennsylvanians who generously shared their time with me—think providers ought to consider when serving the Deaf.

Communication, first and foremost

Adequate communication between healthcare providers and a Deaf or HH consumer can be lengthy and laborious. It takes time to make sure that the client understands her or his diagnosis, medication schedule and dosage, contraindications, and so forth.

For Deaf persons, an interpreter may be the only way that essential information can be communicated. But healthcare providers often balk at hiring them because of the expense. This complication makes for a lot of red tape, some providers insisting that requests for interpreters be made two weeks in advance and some offering interpreters inconsistently.

Without skilled interpreters, however, Deaf clients can leave appointments utterly bewildered.

Jennifer Macioce, Director of Day Treatment & Deaf Services at Milestone Centers, Inc., described the doctor visit of one Deaf woman who wasn’t offered interpreter services. The doctor was confident that she received the information she needed because he typed up his instructions in a nice, long paragraph. She thanked him and left, but later approached Macioce, asking her to interpret it. The woman couldn’t read the paragraph.

This is not uncommon. Many Deaf individuals struggle to read English. Written English is largely based on sound, a linguistic structure that doesn’t make sense to the Deaf.

Furthermore, it’s a misconception among the general public that sign language is signed English; it’s not. ASL has its own syntax , its own idioms, and vocabulary for Deaf experience.

Add to the mix that members of different Deaf communities have their own regional differences in signing, as well as different levels of vocal ability from person to person. The vast range of dialects and abilities presents an enormous challenge to healthcare providers.

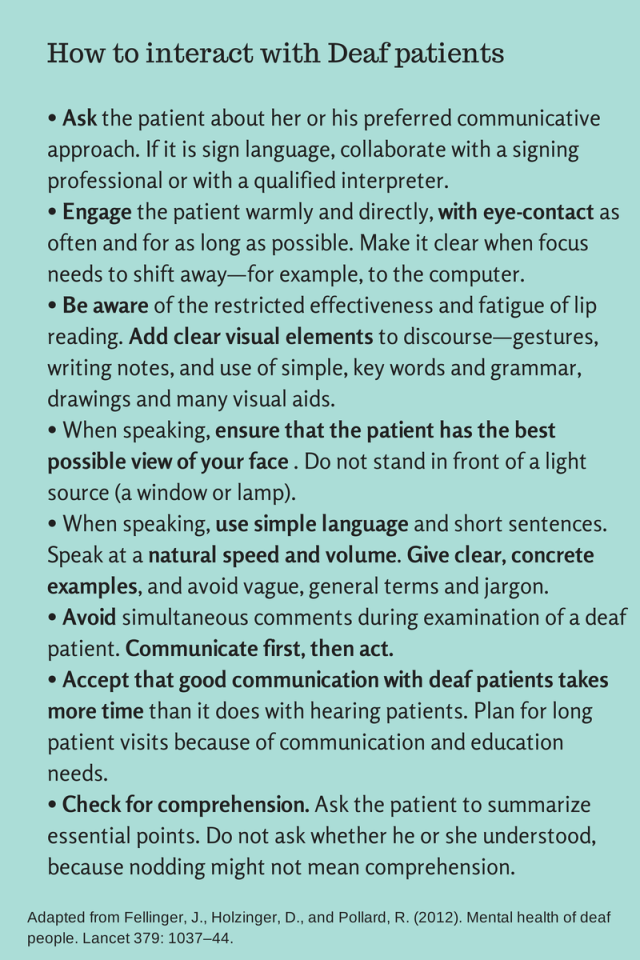

There are a few simple tools to help mitigate the challenges in communication. See the recommendation panel below.

The structure of services

Substance use services for the general public are structured to offer graduated levels of treatment. For most people, there are various levels of care to suit various needs, life circumstances, and levels of addiction. Each level provides the appropriate amount of support to aid in the process of recovery.

These levels include Outpatient, Intensive Outpatient (IOP), Partial Hospitalization, Inpatient, and Residential (also known as Diversion and Acute Stabilization or DAS).

IOP and Partial Hospitalization are particularly important in early stages of recovery as they provide group support and enough structured time during the day to create new patterns of living without substance use. But this level of service does not exist for many Deaf persons in southwest Pennsylvania—or in most of the country, for that matter.

Gretchen Hoffer, LPC is a counselor in the Pittsburgh area specializing in both substance use disorders and therapy for the Deaf and HH. Treatment works, she agrees, when clients are in a residential program, like inpatient or DAS, where they live for up to 30 days. But afterward, there’s no middle ground, no Partial, IOP, or consistent AA/NA meetings to provide daily support.

“After they complete residential treatment, they go to individual therapy only once a week,” she said. “It’s simply not enough.”

Another issue is group therapy, a mainstay in substance abuse treatment, which can present serious challenges for Deaf and HH persons.

Mary-Alice Olson, a Licensed Clinical Social Worker specializing in working with Deaf, Deaf-Blind and HH persons, said that the need for connection with others in treatment is significant, especially in a population that may suffer from mistrust of others and institutions. “A Deaf person may be the only Deaf person in the group at the time,” she explained. “[She or he] will need to use an interpreter just to get the information and by the time the information is relayed, no matter how skilled the interpreter is, the topic has generally moved on to something else.”

Not only that, but even if interpreters are hired for group and individual therapy, they can’t necessarily stick around for interaction during meals or other activities, also a crucial part of forming bonds with others for the recovery process. The resulting isolation for Deaf persons makes it “hard for them to maintain any recovery,” said Olson.

The Deaf community itself

Deafness can be associated with a greater risk of mental health disorders, which, of course, often co-occur with substance use disorders.

“The language and communication environment of the family is a crucial variable affecting psychosocial well-being of deaf children,” say Fellinger, Holzinger and Pollard (2012). Deaf children whose families do not learn to communicate with them are four times more likely to suffer from mental health disorders than those whose families communicate well with them. These children are also more likely to experience cruelty and bullying at school.

And because the Deaf community is relatively small, carving a recovery path may be exponentially harder for a Deaf person.

One of the few Deaf hangouts in Allegheny County, the Pittsburgh Association of the Deaf (PAD), is a bar. This is where “many of the Deaf go to socialize with friends,” said Olson. “If they are working their recovery this could be a trigger for them. But if they do not go, they may limit their social interactions and become isolated, which is also not good.”

“Most hearing people in recovery have choices and options of places to go and people to see,” note Guthmann and Sandberg. “They can realistically develop new friendships in the recovering community. In contrast, many deaf people in recovery are isolated and have a limited circle of sober, deaf friends.”

What’s working: Cultural competence is the core issue

When I asked providers in Allegheny County about licensed services available for the Deaf with substance use issues, they all said, “There’s nothing.”

I asked them next what they would do to make substance abuse services available and effective for Deaf persons. Overwhelmingly they cited the Minnesota Chemical Dependency Program for Deaf and Hard of Hearing Individuals (MCDPDHHI) as the gold standard.

MCDPDHHI is known for what it calls its “cross cultural approach”: its staff are fluent in ASL and understand Deaf culture, aware of the idiosyncratic nature of Deaf communities, ethnic and cultural backgrounds, and mental health needs. They have experience working with substance dependent Deaf and HH persons. They implement “flexible and creative approaches based on the 12 steps of AA/NA,” and emphasize visual approaches to communication and education.

Cultural competence is the core issue, said Hoffer. “Just as service providers receive training for issues related to nationality or culture, gender, and race, they also should become aware of the needs of Deaf and HH as its own distinct culture. There’s so much that the community at large, as well as our healthcare providers, don’t know or understand about the Deaf.”

Conceptualizing deafness as difference rather than pathology or disability, as members of the culturally Deaf community do, is a solid first step to ensuring that Deaf individuals receive the kind of treatment that they need.

Hoffer believes that Southwestern PA could take a leaf out of Minnesota’s book. Building on an already established treatment facility designed for hearing clients may be the best bet in terms of creating a culturally competent unit for treating the Deaf. It would be ideal, she said, to offer a small unit of 4 or 5 beds within a hearing facility and hire staff who can sign and understand Deaf culture—which gets around the added cost of hiring interpreters on an individualized basis.

“Of course,” she exclaimed, “I would even be happy to have a facility that provides interpreters consistently.”

But there are also other solutions on the horizon. Although there has been a downward trend in funding for treatment programs for the Deaf and a number of facilities have closed, internet-based communications and technologies are on the rise and are proving effective.

Hoffer, Olson, Macioce, and Dr. Kimberly Mathos, a psychiatrist who provides behavioral health services for the Deaf in Allegheny County, all cited the CSAT-funded Deaf Off Drugs and Alcohol (DODA) as a program to watch. DODA has had marked success in its behavorial telehealth programs that help consumers and providers alike. Although most of its resources are only available for providers and consumers residing in Ohio, there are possibilities for expansion.

Other good news lies in the realm of screening and assessment. Until recently, a substance use assessment could be very difficult to perform for Deaf persons. With the development of the Substance Abuse Screener in American Sign Language (SAS-ASL) in 2010, a validated computer-based assessment instrument, screening can now be effective and accessible.

Prevention, noted Mathos, in the form of education and screening is where attention needs to turn now. She punctuated our conversation with the thought that developing screening and education in the Western Pennsylvania School for the Deaf might be something to look into next.

“It’s what Debra Guthmann is doing at the California School for the Deaf, Fremont; it’s something we could do here: heading off substance misuse before it becomes the full-blown difficult-to-treat disorder.”

The serenity prayer in ASL. Check out other Deaf Off Drugs and Alcohol (DODA) videos on their Youtube channel

Resources

Center for Hearing and Deaf Services (HDS)

Located in Pittsburgh and Greensburg, Pennsylvania, HDS provides a wide range of services, including interpreting services, behavioral health services, life skills programs, and an assistive device center.

Deaf Off Drugs and Alcohol (DODA)

Helps treatment providers and Deaf and HH consumers in Ohio develop effective communication strategies so communication barriers are removed and treatment can begin

An on-line sign language resource

A valuable resource that provides behavioral health, wellness, advocacy and other information to Deaf, Deaf-Blind, and HH people

Offers specialized and comprehensive mental health services for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing in southwest Pennsylvania. While currently not licensed to treat substance use disorders, they do help provide support to Deaf persons with SUDs and a few of their counselors are in the process of obtaining Co-Occurring Disorders certification. Macioce is certified to treat problem gamblers.

One of their initiatives is called Mental Health First Aid, an evidence-based program that raises awareness about mental illness and is preventative in scope. Typically the courses are offered in either English or Spanish, but Macioce advocated for two Deaf persons to be certified as instructors in the program so that it can be presented in ASL. They are the only Deaf Mental Health First Aid instructors in the nation.

Minnesota Chemical Dependency Program for Deaf and Hard of Hearing Individuals (MCDPDHHI)

A program specifically designed and staffed to meet the needs of Deaf and hard of hearing individual started in 1989

Provides telecommunications services for the deaf and disabled