Opened in 1935, the pastoral prison, rehab, and research center had a major impact on evidence-based practices today

The history of professional addiction treatment in the United States is fairly short and very complicated. As Nancy Campbell, J. P. Olsen, and Luke Walden write in their book, The Narcotic Farm: the Rise and Fall of America’s First Prison for Drug Addicts, the massive prison that housed people dependent on drugs in the middle of the 20th century encapsulates America’s “ambivalence about how to deal with drug addiction.”

The Narcotic Farm was a government-funded prison, rehabilitative center, and research center in Lexington, Kentucky between 1935 and 1974. Its mission was threefold: to understand the hows and whys of drug addiction, rehabilitate persons addicted to drugs completely, and find a permanent cure.

In the latter, it obviously did not succeed. It couldn’t rehabilitate the majority of its inmates either; nearly 90% returned to drug use after walking out of its doors.

As for the hows and whys, there the Narcotic Farm claims some important successes: many of its discoveries are the foundations of substance use treatment today. That knowledge came with an ethical cost.

“Patients” rather than “prisoners”

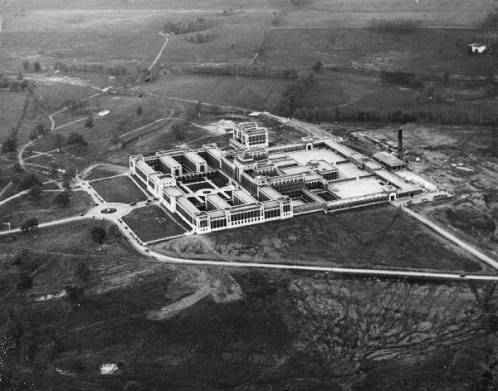

In 1935, the Narcotic Farm opened to much fanfare. The institution was enormous: a monolithic art-deco structure built on 1,000 acres of farmland. It was unusual, too, in that it wasn’t only a prison, but people could also check themselves in of their own volition.

The Denver Post featured the institution in a 1939 story that headlined, “Drug Addicts Have a Future: Great Narcotic Farm Operated by United States Public Health Service Is Achieving Excellent Results.” And in some ways the operation of the prison seems idyllic: male patients tilled the ground, harvested crops, milked cows, and raised pigs and female patients cooked, sewed, and laundered. Food was produced and cooked on site, with such notable patients as William S. Burroughs remarking that the meals were “excellent”(Campbell, Olsen & Walden p. 95).

Recreation was also an important aspect of treatment for patients and prisoners alike. Team sports were encouraged and there were tennis courts, fields for sports, a bowling alley, and art therapy. Narco, as it was known to locals, is perhaps most famous for its music, as many jazz greats of the day including Sonny Rollins, Chet Baker, and Elvin Jones, checked themselves in. Patients played free concerts for other patients and the public (unfortunately, there are no existing recordings).

“The first lesson that everyone can immediately glean from history of ‘Lex’ is that farm work doesn’t cure addiction.”

Patients received manicures and pedicures, had their hair cut and styled and were taught how to take care of themselves. All of this was in the service of a kind of moral therapy, a 19th century-inspired concept: if one’s environment is transformed to be natural, pastoral, wholesome–then one is likewise transformed.

As news of the Narcotic Farm spread through the media, its structure and mission had the effect of changing popular misconceptions about people who became addicted to drugs: they weren’t the “degenerate prisoners” of the popular imagination, or even less intelligent, but ordinary people with very human problems.

This was all good on the surface, but the approach to treatment didn’t seem to work. J. Spillane writes that the “location of the hospital on a self-sufficient farm in a rural environment was a key feature of its design” and “Agricultural labor was considered integral to the Cure,” but that physical labor wasn’t successful in preventing relapse or promoting recovery. “The first lesson that everyone can immediately glean from the history of ‘Lex’ is that farm work doesn’t cure addiction,” says Spillane.

Over the years, the Narcotic Farm experimented with other treatment models, including Synanon. For more on that, see Points: the Blog of the Alcohol and Drugs History Society, Lessons from the Narcotic Farm, Part Five: Matrix House

ARC: “Unique access to human subjects”

Treatment models weren’t the only areas in which the Narcotic Farm experimented. The institution is even more well-known—or notorious—for its addiction research on volunteer inmates and residents.

The Addiction Research Center (ARC) operated as part of Lexington from 1948 to 1976. At the time, it was “the only place in the world where abuse potential was assessed in human beings” (Campbell, Olsen & Walden, p. 26).

According to NIDA, the discoveries and contributions of ARC included:

- Advancing the use of methadone to treat heroin addiction

- Helping explain why so many addicted people undergo repeated relapses to drug abuse even after successful treatment

- Demonstrating that drug dependence is not limited to opiates and extends to other drugs of abuse

- Helping find and study multiple opioid receptors, the binding sites in the nervous system where heroin and other opiates unleash their effects

- Recognizing the significance of opioid antagonists for opiate abuse treatment and research as well as developing an opioid antagonist as a lifesaving antidote for heroin overdoses

- Developing abuse liability studies and criteria to help scientists determine whether new pharmaceutical products might bear potential for treating addiction and abuse

- Profiling the physiological and psychological effects of classes of drugs-including sedatives, hypnotics, hallucinogens, and marijuana-to provide basic tools for continuing research on and evaluation of drugs

In addition, one of its greatest contributions to the realm of public health was the center’s precept that “addiction is a chronic, relapsing disease.” (Campbell, Olsen & Walden, p. 166).

But there were ethical concerns to ARC’s research. This was entirely new territory at the time and there were no strictures in place to prevent research on prisoners. Because ARC’s researchers maintained experiments on a volunteer basis and tended to use those who had repeatedly relapsed, the work went unquestioned for some time. But the practice of offering persons in recovery from addiction their drug of choice in exchange for participation in experiments—a “payment” in drugs—began to raise some eyebrows.

Many of its discoveries are the foundations of substance use treatment today. That knowledge came with an ethical cost.

The methods of experimentation were questionable also. In an interview with National Public Radio Nancy Campbell explains that ARC would “re-addict” what the researchers called “post-addicts” to an opiate and then begin to withdraw them, administering new drugs to see how effective they were in ameliorating withdrawal symptoms.

ARC is also known for its involvement with the MK-ULTRA program (the CIA’s infamous mind-control drug experiments) during which the ARC director received CIA money for LSD research. It was after this scandal that ARC’s fate was sealed. On December 31, 1976, the last subject was transferred out of the lab.

After the Senate hearings initiated by Sen. Edward Kennedy on human experimentation in the 70s, it was determined that prisoners could not freely choose to be subjects; the fact of incarceration precluded free choice. As a former subject in tests run at ARC, Eddie Flowers commented, “Later on I came to grips with the fact that I was used. Being a young man, I was very vulnerable in the sense that if it’s about drugs, I wanted drugs.” (Campbell, Olsen & Walden, p. 165)

Learning from history

The Narcotic Farm is a giant player in the history of addiction treatment and in the way practitioners address addiction today. Here at IRETA we work to propagate evidence-based treatment, many of those treatment practices directly derived from the Narcotic Farm.

Although Narco is often remembered for its part in the MK-ULTRA scandal and experimentation on prisoners, as Campbell emphasizes, the scientists there “saw themselves as protectors of public health.” Their findings prevented more seriously addictive drugs from going on the market, she added.

And as Spillane points out, “at any one given moment during Lexington’s first three decades there were FAR more addicts sitting in big-city jails, where squalid conditions predominated and treatment was minimal or nonexistent.”

More than just a sensational chapter in the relatively young history of substance use disorder treatment, the Narcotic Farm gives us a window into how difficult it is to navigate the waters of research in addiction and its treatment.

Psychiatrist (and former patient at Lexington) David Deitch has said that the Narcotic Farm embodies America’s “schizophrenia” about how to deal with addiction. Is it a social problem? A medical problem? At times, the Narcotic Farm used each of those lenses. And either lens brought hazards and benefits.

Experiences at Narco illustrate that whether we choose to address addiction, at any given moment, as a social or medical issue can lead to more or less humane treatment, more or less productive research, and more or less health benefit to the individual or the society. And each viewpoint brings its own serious ethical pitfalls.

Recommended Resources

The excellent “Lessons from the Narcotic Farm” series on the Points ADHS blog