Physicians need not be so hesitant to prescribe buprenorphine—there are models of care to support them

When it comes to providing treatment with buprenorphine, primary care providers fear an onslaught. Many are concerned that the minute word gets out that that they’re a waivered buprenorphine prescriber, the waiting room will be full. And the patients will have overwhelmingly complex needs.

This fear was illustrated by a 2014 study of physicians in Washington State who had been recruited to receive training that would enable them to obtain a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine. Interestingly, all of these physicians reported positive attitudes toward buprenorphine treatment. However, what happened after the training was quite telling.

– Only 50% actually obtained their waiver

– Only 22% actually began prescribing buprenorphine

– And only 9% placed their name on the SAMHSA buprenorphine treatment locator, so that patients could actually find them.

Physicians’ reluctance to prescribe buprenorphine has been observed for nearly twenty years, since the drug became available in the U.S. Expanding the number of patients that physicians can treat hasn’t yielded results. Although physicians can now treat up to 275 patients with buprenorphine (up from 100 in 2016), most physicians treat less than 30.

The Need

About three-quarters of metropolitan counties have at least one physician with a buprenorphine waiver. That doesn’t mean that the physician is accepting new patients, or ensuring that treatment is affordable—just that a physician exists within most urban counties.

Availability changes radically outside of cities. A study published in 2015 showed that 60% of suburban counties, 53% of counties with small towns, and 82% of rural counties do not have a single buprenorphine prescriber.

Buprenorphine Works

The big problem with such limited access to buprenorphine is that buprenorphine works.

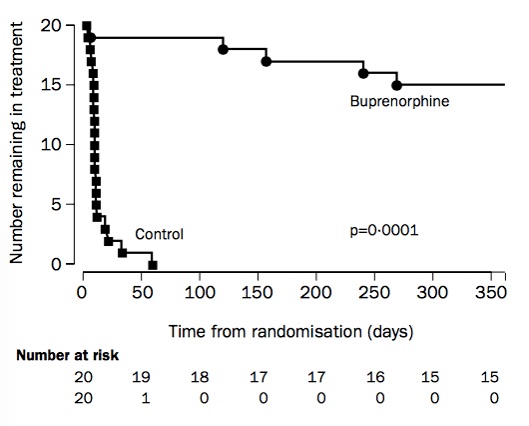

In this case, a picture truly is worth 1,000 words.

The graph above illustrates the results of a 2003 randomized controlled trial of treatment for 40 individuals with opioid use disorder. The control group received a placebo medication, but came to a treatment center daily to receive doses and cognitive behavioral therapy. The buprenorphine group also traveled to a clinic daily to receive medication and counseling.

The differences are dramatic. One-year retention in treatment was 75% and 0% in the buprenorphine and placebo groups, respectively. Most members of the control group disengaged from treatment in less than a month. Most importantly, four members of the control group died from overdose within one year, while no members of the experimental group died.

The evidence goes far beyond a single study. A Cochrane review of 31 trials concluded that there is “high quality of evidence” that buprenorphine is “superior to placebo medication in retention of participants in treatment at all doses.”

Two Models

In light of the decades-long hesitation to prescribe buprenorphine in primary care settings—and its clear effectiveness in treating opioid use disorder—Julie Kmiec, DO, led a webinar for IRETA on ways to expand buprenorphine treatment in primary care. The webinar is available for on-demand viewing in our Webinar Library.

In the webinar, Kmiec discussed two existing models of care that can help overcome some of the practical barriers to buprenorphine prescribing that concern physicians.

The Massachusetts Model

The Massachusetts Model was developed because “we did not see docs getting waivered enough to match the treatment needs in our state,” said Hillary Jacobs, a policy adviser with the Massachusetts Dept. of Public Health.

When surveys revealed that physicians were not providing buprenorphine treatment because they felt they did not have enough nursing support to care for patients with opioid use disorders, Massachusetts devised a model of care that revolves around the work of a nurse care manager, rather than a physician.

Nurse care managers are RNs who provide overall coordination of care for patients receiving buprenorphine. They supervise medication induction, follow up with patients, collaborate with other providers, and troubleshoot problems that arise.

A large observational study showed that patients who received treatment through this model did as well as patients who received it using a physician-centered model. It also helped expand the number of primary care providers who were prescribing buprenorphine in Massachusetts.

The practices that implemented this model received support from Boston Medical Center, which could provide on-demand technical assistance via cell phone. They could also provide support when the health centers were preparing for a DEA audit.

Vermont Hub and Spoke

Like Massachusetts (and every other state), the demand for opioid use disorder treatment in Vermont outweighed the supply.

Vermont’s solution was to create five central induction sites with a high level of buprenorphine expertise (the “hubs”) and a network of buprenorphine prescribers (the “spokes”). The theory is that induction can be a complex process, and that specialized hubs can provide more intensive services to new patients. Once a patient has achieved more stability, he or she can be referred to the “spokes,” who are primary care providers with waivers to prescribe buprenorphine.

The “hubs” provide support for the “spokes” in Vermont, in that the experts who work at the induction sites are available for case consultation and additional technical assistance whenever private physicians need it.

This model has succeeded in increasing Vermont’s buprenorphine treatment capacity. From 2012 to 2016, there was a 64% increase in waivered physicians and 50% increase in the number of patients served per waivered physician.

Support is Key—and Support is Available

The success of the Massachusetts and Vermont models are evidence that buprenorphine access can be expanded, but that support for physicians is key. Both models provide on-demand expertise to help with screening, drug testing, complex cases, referrals to other providers, and numerous questions that buprenorphine prescribers may encounter.

Fortunately, even for physicians working outside these two model programs, support is available.

Providers Clinical Support System

The Providers Clinical Support System (PCSS) offers buprenorphine waiver training, webinars, and one-on-one coaching. They also host an active discussion board where less-experienced physicians ask questions that are quickly answered by longtime buprenorphine prescribers.

Project Echo

Like PCSS, Project Echo provides free support in the form of training and clinical consultation. Everything is supplied remotely, so providers from all over the country (especially underserved areas) can benefit from this program.

Clinical Guidelines

Although a book may be less helpful than a real person when questions arise, sometimes a book does the job. These are free online:

Medications for Opioid Use Disorder (TIP 63): This guideline was released in 2018 and includes information from specialty addiction providers and healthcare professionals

Buprenorphine: A Guide for Nurses (TAP 30): This guideline was released in 2009 and is specifically targeted at nurses. Note that nurse practitioners can now prescribe buprenorphine, although they could not when this guideline was released.

Clinical Guidance for Treating Pregnant and Parenting Women with Opioid Use Disorder and Their Children: This guideline was released in 2018 and includes a series of helpful fact sheets on issues pertaining to pregnancy and parenting.