Every October, we recognize National Addiction Treatment Week, which promotes awareness that:

1. Addiction is a disease.

2. Evidence-based treatments are available.

3. Recovery is possible.

All true. All important.

But if we are going to address the public health impact of substance use and addiction, we need to think more clearly about the role that addiction treatment has to play in improving individual and community health. And that means we need to take a closer look at what is known as the “Treatment Gap.”

What is the ‘Treatment Gap’?

The treatment gap is the difference between people who need addiction treatment and those who actually receive it. A common statistic says that “Only about 1 in 10 people who need treatment actually get it.” But what does that mean and where does it come from?

The origin of this well-known statistic is the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), which is an annual survey of Americans’ substance use patterns and mental health issues. NSDUH results from 2018 show that about 7.8% of Americans age 12 and older needed substance use treatment in the past year. Also in 2018, only about 11% of that population received specialty treatment services, approximately 1 in 10.

What Does it Mean to ‘Need Treatment’ According to the NSDUH?

You’re probably wondering, “What does it mean to ‘need’ treatment and how does the NSDUH measure that?”

The survey includes questions that are based on a (now outdated) diagnostic criteria contained within the DSM-IV guide. The new DSM-5 is the current standard for diagnosing addiction, but the NSDUH retains the old questions for the sake of continuity. If the respondent answers “yes” to three or more of these criteria, they are considered to “need treatment.”

1. Spent a great deal of time over a period of a month getting, using, or getting over the effects of the substance

2. Used the substance more often than intended or was unable to keep set limits on the substance use

3. Needed to use the substance more than before to get desired effects or noticed that the same amount of substance use had less effect than before

4. Inability to cut down or stop using the substance every time the individual tried or wanted to

5. Continued to use the substance even though it was causing problems with emotions, nerves, mental health, or physical problems

6. The substance use reduced or eliminated involvement or participation in important activities

7. [In the case of alcohol, opioids, and other drugs with clear withdrawal syndromes, the survey includes a question about experiencing withdrawal symptoms]

Even if they do not answer “yes” to three of the above criteria, the NSDUH categorizes the respondent as “needing treatment” if they answer “yes” to one of the following criteria:

1. Serious problems at home, work, or school caused by the substance, such as neglecting your children, missing work or school, doing a poor job at work or school, or losing a job or dropping out of school

2. Used the substance regularly and then did something that might have put you in physical danger

3. Use of the substance caused you to do things that repeatedly got you in trouble with the law

4. Had problems with family or friends that were probably caused by using the substance and continued to use the substance even though you thought the substance use caused these problems

What Causes the Treatment Gap?

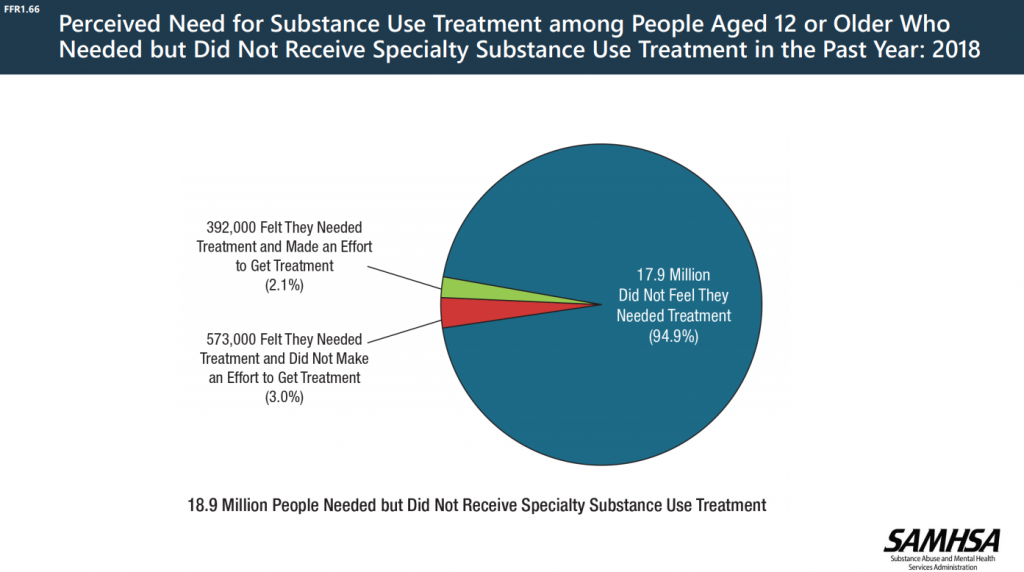

This is where the NSDUH results really get interesting–and where they stay consistent, year after year. Take a look at this graph, which is pulled from the 2018 NSDUH:

In 2018, of the 18.9 million people who needed but did not receive treatment–the ones who we’d describe as having fallen into the treatment gap–95% did not feel they needed treatment. This graph looked nearly identical in 2017, 2016, and so on.

These were not individuals haggling with their insurance companies or waiting on hold for hours with local rehab facilities. It’s not that they lack phones, internet access, or transportation preventing them from getting the help that they need. They simply don’t agree with the government’s assessment of their need for addiction treatment.

In a nutshell, the treatment gap is the result of a perception problem, not an access problem.

Now That We Know the Real Cause of the Treatment Gap, What Can We Do About It?

As Americans become more aware of the consequences of substance use (especially dramatic consequences like overdose deaths among relatively young people), it’s natural to interpret the solution to the oft-quoted treatment gap as “more treatment.” However, the fact that most Americans who ostensibly need help with substance use don’t perceive a need for treatment suggests that simply expanding treatment access will have little impact on public health.

This is not to say that the 7.8% of Americans that the NSDUH categorizes as “needing treatment” don’t have significant issues with drug and alcohol use. If a person is having trouble cutting back on their use, experiencing significant interference with their professional or personal obligations, or struggling with withdrawal symptoms, they probably do have some type of substance use disorder and might really benefit from some help. The question is: what kind of help would members of this group see as acceptable? If in their minds, they don’t need specialty treatment services, what would they say they need?

Here are several strategies that might actually help close the treatment gap, rather than simply expanding access to the same type of treatment services that we currently have:

Earlier interventions in a variety of settings. Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) is an evidence-based approach to identifying and addressing unhealthy substance use that can be implemented in primary care, emergency departments, mental health agencies, and dozens of other settings. Right now, a very small percentage of patients talk with their primary care provider about alcohol use and even fewer talk about other drug use. SBIRT has been shown to help patients reduce their alcohol use. Done correctly, it can create an ongoing alliance between health providers and their patients to recognize and address unhealthy substance use over time.

More addiction treatment in non-specialty settings. Your doctor can treat your alcohol use disorder–did you know that? Not only can your doctor prescribe several FDA-approved medications for alcohol, but there are medications that are designed to help patients reduce (and not completely stop) drinking. This is a great option for patients who would like discrete support and are ambivalent about abstinence. Doctors can also treat opioid use disorder with several FDA-approved medications. However, since primary care doctors rarely inquire about substance use (see above), they often don’t recognize when a patient might benefit from these treatments. Furthermore, most PCPs are woefully under-educated about the medications they can prescribe for substance use disorders.

More flexible, person-centered treatment options. The average American imagines “specialty addiction treatment” as a 28-day rehab. “That might work for Lindsay Lohan, but I have a job,” you might think. In reality, outpatient treatment works about as well for most people with addiction, which offers flexibility with work, childcare, and other common responsibilities. However, in addition to treatment options that accommodate our schedules, Americans need treatment options that fit with their goals. And for many of us (even those of us who have struggled with our substance use) that goal is not total abstinence. However, very few treatment providers offer a moderation- or harm reduction-based approach to substance use services. If we want to close the treatment gap, we have to provide the kind of treatment that people want.

Consistent messages that fight stigma and pessimism about addiction. People that see addiction as a personal failure rather than a brain disorder are less likely to seek help for it. People that never see examples of recovery are unlikely to believe in that possibility for themselves, which makes treatment-seeking seem futile. Negative and inaccurate messages about the nature of addiction and the possibility of recovery do contribute to the treatment gap.

And that means we can all help in some small ways: share the important and accurate messages that proponents of addiction treatment preach:

1. Addiction is a disease.

2. Evidence-based treatments are available.

3. Recovery is possible.

Additional Resources

Results of the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health

Description of the methodology of the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health