Sort of amazingly, research on SBIRT for risky substance use in mental health settings is scant. That’s why we’re excited about a large randomized clinical trial that UCLA kicked off last year.

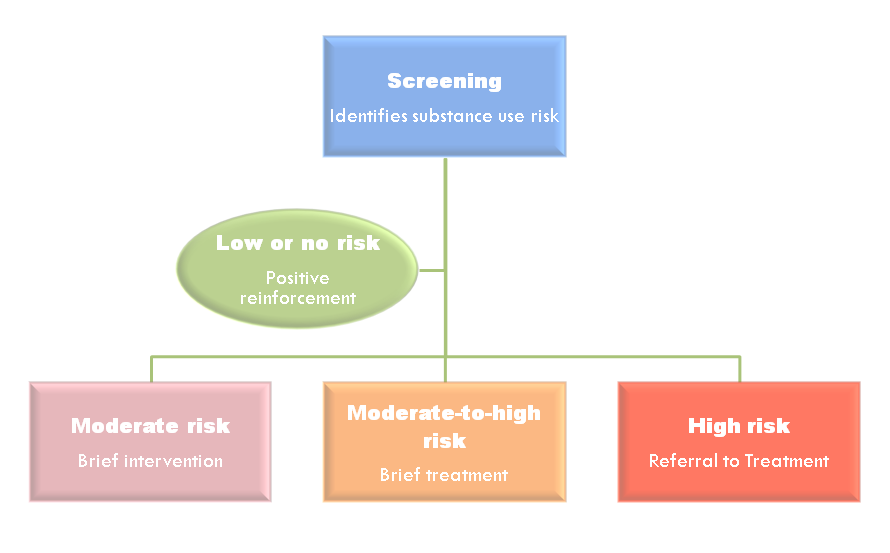

SBIRT (Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment) is an evidence-based public health approach to identifying and providing brief counseling for those who use alcohol or other drugs at risky levels.

Here’s how it works: a health practitioner screens a patient for risky use with a short questionnaire (like the AUDIT, DAST-10, or ASSIST). If the patient screens for moderate risky use, a brief intervention or brief treatment may follow. If the patient screens for severe risk, a referral to treatment may be indicated.

For over a decade, there has been a lot of energy dedicated to using SBIRT in primary care and hospital settings. That’s where SBIRT has largely been implemented.

But there hasn’t been quite the same focus on research or implementation of SBIRT into mental health care settings. A strange absence of research literature and implementation efforts persists regarding SBIRT in mental health care: how does it help, when and where should it be implemented, how effective is it in getting proper treatment to the people who need it?

In 2013, 7.7 million adults in the United States had co-occurring substance use and mental health disorders. Both mental health and addiction treatment providers see the interplay between these two behavioral health conditions every day. It seems common sense, then, to incorporate a validated screening and intervention process into mental health intakes, assessments, and reassessments.

Results of fledgling research

There are a few initial studies that suggest that SBIRT in mental health settings could effectively address clients’ risky substance use.

In mental health care for adolescents, the use of SBIRT has been shown to be effective for teens with co-occurring disorders. According to one study, adolescents who were identified in a mental health care setting as having a co-occurring disorder were more likely to initiate treatment than teens identified in primary care settings.

This suggests that the therapeutic alliance between clients and their therapists may encourage clients’ responsiveness to interventions like SBIRT.

In another study, researchers looked at how structured alcohol and drug screening using the ASSIST (a tool developed by the World Health Organization) was implemented at a university campus mental health center.

The results of that study showed that implementation of screening at university mental health centers is feasible, and that there are a number of advantages to doing it. For instance, undergoing a screen provided an opportunity for students to talk about substance use and helping clinicians determine whether substance use is a contributing factor to their presenting problem.

Large study underway at UCLA

Researchers in the Integrated Substance Abuse Programs at UCLA are hoping that some of the questions surrounding the efficacy of SBIRT in mental health settings will be answered in their five-year study currently underway.

The study, funded by National Institutes of Health (NIH) through the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), is in its beginning stages. It will recruit and follow 1,000 adults under psychiatric care in both inpatient and outpatient mental health settings.

Participants will be screened and—if eligible—randomly assigned to one of two groups: SBIRT Intervention group, in which participants will receive brief intervention and referral to treatment, as indicated; or Health Education group, in which participants will receive an education session, informational materials and a contact list for addiction treatment programs.

Of particular interest to researchers is how and why SBIRT might be effective at reaching more than just those with severe SUDs. Dr. Suzette Glasner-Edwards, one of the Principal Investigators of the study, notes that the clients who receive referrals from mental health providers are usually those presenting with severe SUDs, which can often interfere with their ability to follow treatment plans for their mental health disorder.

But those who present with mild or moderate SUDs are sometimes not on the radar. “‘Risky substance use does not appear to be a major focus,” she said. “This is one area where SBIRT could be expected to have an impact, as about half of those we have recruited thus far fit into the moderate risk category.”

Dr. Peter Luongo, Executive Director of Institute for Research, Education and Training in Addictions (IRETA), sees the necessity of more research on SBIRT efficacy and implementation. “We need more studies like the one being conducted by the ISAP at UCLA to help us better understand if the SBIRT model can be effective if extended to different populations and settings, “ he said.

“Hopefully,” he added, “NIDA will continue to support SBIRT research for the foreseeable future.”

References and resources

SBIRT In Mental Health Settings study at the Integrated Substance Abuse Programs at UCLA

IRETA is the federally-funded National SBIRT Addiction Technology Transfer Center (SBIRT ATTC), which provides SBIRT resources and training to health and human service providers nationwide. For more information,

- Visit IRETA’s SBIRT Key Resources, our short-list of places to go to learn about SBIRT

- Visit our partners at the BIG Initiative and Expanding SBIRT to Hospitals

- Check out our Webinar Library, which includes a long list of SBIRT-related trainings conducted over the last two years

- Read stories on the IRETA Blog about SBIRT in the real world, including SBIRT in hospitals, SBIRT in FQHCs, and SBIRT in primary care

- Download training manuals and other products related to SBIRT in our Free Downloads

- Look through our SBIRT Toolkit for Practice for hands-on tools you can use

IRETA, through other funded projects, currently oversees SBIRT projects tailored to various settings, such as nursing schools, federally qualified healthcare centers, and emergency rooms, among others. Read more about our SBIRT projects